Bo Winegard recently published “The Case for Race Realism”, a defense of the belief that race is a biological category and that races differ behaviorally and cognitively for primarily genetic reasons, in online newsletter Aporia (where Winegard is executive editor). I made the unfortunate mistake of reading it. The article is a reposting of the same article Winegard wrote back in June this year, which itself was a warmed-over version of his 2021 academic paper “Dodging Darwin”, which more or less rehashed another academic paper he wrote in 2017, loosely based on a 2016 article for Quillette, all of which are mostly just restatements of arguments made even earlier by the notorious Arthur Jensen.

The piece is filled to the brim with the usual common refrains: that a pall of orthodoxy abandons Darwin’s theory of evolution by rejecting that race is a meaningful biological category reflecting human’s evolutionary history, denying that natural selection led to a substantial causal role of genes in behavioral and cognitive differences among races, stifling debate with a “fleet of moral accusations and (plausible) threats of perpetual unemployment”, and “promoting animosity against whites”. Racial hereditarianism, on the contrary, accepts these as facts “supported both by theory and by the abundance of available evidence”.

Recently, my coauthors and I have challenged this exact claim that hereditarianism is the true evolutionary approach to human variation. In Roseman and Bird (2023) we conclude that the:

lack of connection between evolutionary theory and data through methods that are constructed in a theoretically informed way means the evolutionary statements in the hereditarian literature are products of nothing more than post hoc exercises in a-theoretical verbal interpretation. This renders the hereditarian complaint of being excluded from mainstream social and evolutionary sciences on account of their application of evolutionary thought moot because there is no such application of evolutionary thought in the first place.

and in Bird, Jackson Jr., and Winston (In Press) we argue:

While [racial hereditarian research] psychologists claim to embed their work in biology, RHR is pseudo-quantitative analysis, which only appears to be grounded in the advanced quantitative methods of genetics and evolution. In fact, it bears no resemblance to those sciences.

If Winegard’s article is truly meant to represent the best summary of the case for hereditarianism, then, to my surprise, our strong accusations were in fact being too generous to hereditarians. They not only ignore evolutionary theory and developments in methodology in genetics and evolutionary biology, they flat-out ignore their critics who attempt to engage them in the debates they profess to desire!

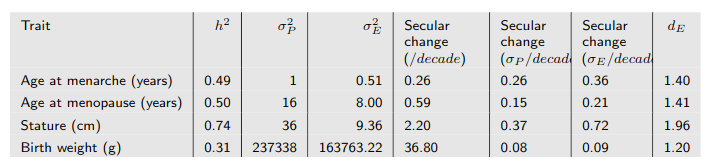

The two specific examples of data and theory supporting hereditarianism that Winegard discussed are the high heritability of IQ within racial groups and studies that correlate IQ scores with estimates of the amount of “European ancestry” in admixed individuals. He hits all the greatest hits: Lewontin’s famous thought experiment to highlight the disconnect between the causes of variation within groups and between groups is a special case that doesn’t apply to the real-world example of racial IQ disparities. Winegard apparently did not feel the need to update the article with an acknowledgment that two recent papers, one by Josh Schraiber and Doc Edge at USC and the other by myself and Charles Roseman, have now shown that Lewontin’s thought experiment is not a special case and that there is no relationship between heritability within groups and between groups. While both articles were posted within the last two months, neither argument is new. Feldman and Lewontin first made the point, albeit less in-depth, in 1976. Winegard then invokes Arthur Jensen’s argument that “As within-group heritability increases, the size of the required environmental difference to account for between-group differences also increases”. In Roseman and Bird, we show that Jensen’s formulation is mathematically and conceptually flawed. The table below punctuates that neither Jensen’s formula (dE) nor heritability (h2) relates to secular changes in several human traits. Winegard’s claim that the high heritability of a trait that differs between populations can reasonably be assumed to have a genetic cause for group differences is not a reliable heuristic, it’s entirely divorced from any evolutionary theory or empirical data.

When discussing studies that correlate IQ scores with the proportion of “European ancestry”, Winegard suggests a positive correlation has a straight-forward causal interpretation, or at least that concerns can be addressed by adding control variables. However, Schraiber and Edge analytically showed the problems with the approach are much more severe. When there is confounding between genetic ancestry and environmental effects, as is undoubtedly the case for Black Americans (See Bird, Jackson Jr., and Winston for an overview of likely factors), the correlation between a trait and genetic ancestry represents the combined effect of genetic and environmental factors and it is impossible to separate the two to identify their relative contribution or even the direction of their effect. Like in the case of within-group heritability, there is no way to get information about the causes of group differences from these analyses, meaning admixture correlation studies are fundamentally unable to provide evidence in support of hereditarianism. Winegard does not acknowledge this critical shortcoming.

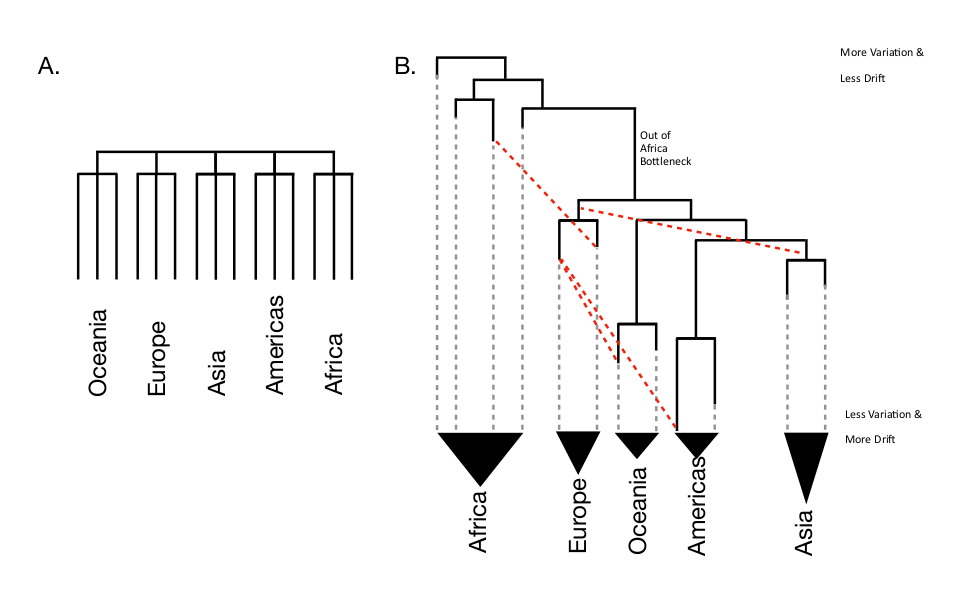

Perhaps Winegard can be forgiven for these oversights since the two papers were posted on Biorxiv so recently (though we notified him via Twitter of these papers). Unfortunately, this pattern of ignoring critics permeates virtually every part of the article. In defending the biological reality of race, Winegard argues that race relies upon “evolutionary history, genetic profiles, and phenotypic profiles” and invokes the “Lewontin’s fallacy”. These exact points were under contention in a 2021 paper by Charles Roseman. Roseman specifically criticized Winegard’s “Dodging Darwin” article’s defense of race realism on the grounds that the racial model (Panel A, below) for which he advocates has been unambiguously rejected by decades of rigorous statistical comparison to non-racial evolutionary models (Panel B, below) (e.g. Long and Kittles, 2003, Long et al. 2009; Hunley et al. 2016). These results show racial taxonomy does not accurately reflect the evolutionary relationships of human populations or fit observed patterns of genetic variation. It is, therefore, an actively misleading model of human variation and a hindrance to proper evolutionary analyses. As Roseman demonstrates, it is hereditarians, not Lewontin, who ignore or mislead about the correlational structure of human variation. Roseman’s paper and this entire body of work is entirely unmentioned in Winegard’s article, opting instead to make a series of strained arguments from analogy.

Winegard chastises hereditarian critics for denying the possibility of natural selection creating behavioral and psychological group differences. He offers no direct evidence himself that such selection occurred, only references to a few cases of local adaptation of physical traits in humans. In fact, he actively ignores my own paper (Bird, 2021) which presents strong evidence from genetic tests for selection that there has been no divergent selection on cognitive ability between African and European populations and concludes

Given the lack of evidence for selection demonstrated here, it is imperative to revise previous speculation about the contribution of natural selection to the global variation in cognitive traits (Winegard et al., 2017; Winegard et al., 2020).

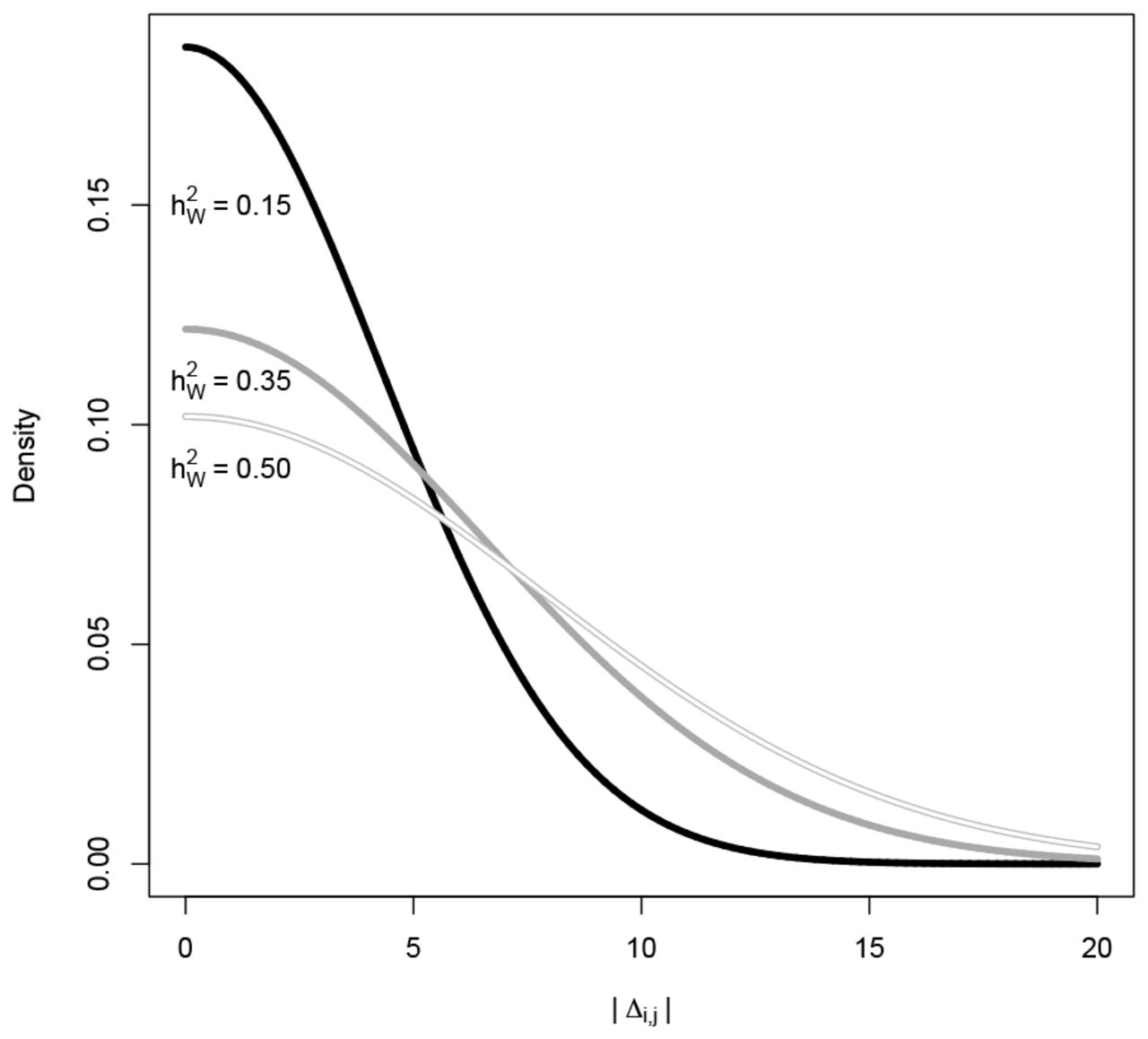

The growing number of population genomic studies showing similar results are also not mentioned (e.g. Guo et al. 2018, Racimo et al. 2018; Howe et al. 2022). What is mentioned is a table of allele frequency differences in single-nucleotide polymorphisms identified by genome-wide association studies from Charles Murray’s book Human Diversity. This analysis is devoid of any evolutionary theory and can not say anything about the magnitude or direction of genetic effects on group differences. Under neutral evolution, the expected difference in mean genetic value between two populations is zero, and the absolute difference is expected to be proportional to the average genome-wide Fst and it can favor either group with equal probability. In Roseman and Bird (2023), we calculate the probability density function of the absolute phenotypic difference for IQ under neutral phenotypic evolution, shown in the figure below. It shows that the bulk of the probability density is at low values, meaning in the absence of strong natural selection acting to differentiate populations, large phenotypic differences between groups will rarely occur. Instead of engaging with this evolutionary-theory-grounded work, Winegard obscures the matter with post hoc exercises in a-theoretical verbal interpretation.

It doesn’t even seem as though hereditarians read or engage with their own fellow travelers. Winegard describes hereditarianism as claiming “genes account for a significant proportion of between-group differences (21% or above)”, however, Jensen and Rushton in 2005 describe the hereditarian position is racial IQ differences being 50% or more due to genetics. In a reply to critics, the “default hypothesis” is bumped up to 80% genetic and 20% environmental. Winegard is not alone, in a recent paper, Russel Warne retreats to an even lower value of anything >0% supporting hereditarianism. For a position that is so strongly supported, according to hereditarians, it seems they can’t even agree on fundamental starting points.

It’s admittedly frustrating to devote the time and effort to author and publish scientific papers that treat these unscrupulous theories seriously, in the spirit of scientific debate. Doubly so when, for all the noise hereditarians make about being stifled and wanting debate, their response is to bury their head in the sand and pretend it never happened. It should make even the most credulous person skeptical that their expressed desire for debate is sincere. If there’s one thing I agree with Winegard on it’s that “self-imposed ignorance, even if motivated by moral sensitivity, is unlikely to help.” In an ironic twist, it is hereditarians who are the victims of self-imposed ignorance. If the case for race realism depends on never engaging with the arguments made against your position, it simply isn’t a good case.