Epistasis and Gene Networks

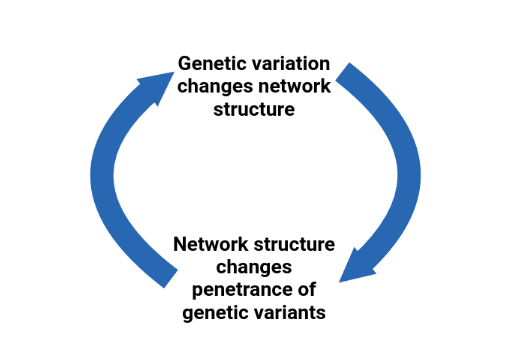

For living things to survive they must appropriately respond to changes in the environment or from genetic mutations. This is especially true for plants, where physically moving away from environmental stresses is not always possible. Being able to maintain vital functions in the face of mutations or environmental change is called robustness. Organisms must also be able to adapt to changing environments through natural selection and to do this mutations need to produce a heritable change in phenotype. How organisms can be both robust to mutations and able to adaptively evolve to new environments has been difficult to answer.

I focus on how interactions among genes change the effect of a mutation, sometimes preventing harmful effects and other times producing a change that may help adapt to a new environment. I also explore how mutations can change the way genes interact with each other. I use the latest technologies, including genomic sequencing and CRISPR gene editing, to study how interactions among genes change between wild plants in the model species Arabidopsis thaliana as well as the crop plant Brassica oleracea (broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage) and the biofuel crop Camelina sativa. These results will help us understand more about the processes of evolution so we can harness this knowledge for plant breeding and conservation efforts to respond to rapidly changing climates.

Pangenomics and Genomic Variation

It’s now recognized that a single reference genome is not sufficient to capture all the genomic diversity within a species. A pangenome provides a better picture of structural and gene content variation that a species harbors through the generation of multiple genomes from diverse lines within a species. Pangenomic analyses have revealed that in some species upwards of 50% of all genes are not found in all individuals and many GWAS lead SNPs in Arabidopsis thaliana have recently been shown to be reflective of structural variation not captured by the reference genome.

I’m interested in using constructing and analyzing pangenomes to characterize structural, gene content, transposable element, and regulatory sequence variation to better understand the evolutionary forces shaping genomes and the role that complex genomic variation plays in ecological divergence and adaptive evolution. These results will aid in the dissection of agriculturally relevant traits to improve crop plants, and open doors for interrogating patterns of among- and within-species genomic variation to gain more insight into genome evolution.

Polyploid Genome Evolution and Evolutionary Constraints

Polyploidy plays a major role in the evolution of novel traits. By producing raw genetic material, evolution is able to explore the phenotype space, as evidenced by the repeated occurrence of whole-genome duplication (WGD) events before the evolution of key novel traits like the vertebra and flowers. This pattern of antecedence is particularly true for species that underwent hybridization prior to genome duplication, a phenomenon known as allopolyploidy. These genomic events exert major constraints on the evolution of genomes, like asymmetric gene loss from subgenomes and preferential retention of genes sensitive to copy number changes, that constrain the genome as it reverts to a diploid state.

Subgenome Dominance

When an organism doubles its genome it experiences a ‘genomic shock’ as it quickly tries to get back to a happy, stable genomic state. Ultimately this process leads to the polyploid organism ‘diploidizing’ and returning to what appears to be a diploid state. In reality this ‘diploid’ state can have vastly different genomic architecture due to fractionation (gene loss) of the different subgenomes. In some species, instead of having subgenomes fractionated at similar rates, one subgenome tends to have more genes lost than the other, a phenomenon called subgenome dominance.

In early stages after whole-genome duplication, genes from one progenitor genome (subgenome) have, on average, higher gene expression (subgenome expression dominance) and/or lower levels of certain epigenetic regulation. Over long evolutionary time, duplicate genes from the dominant subgenome are lost at a much lower rate than other subgenomes, producing a bias in gene content. My work used combinations of genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic data to test for the presence of subgenome dominance in polyploid species and to see the extent to which subgenome dominance is related to the pre-existing differences between the parental genomes.

Future directions for this work include investigating subgenome dominance and spatial and temporal partitioning in gene coexpression networks and the evolutionary consequences of subgenome dominance.

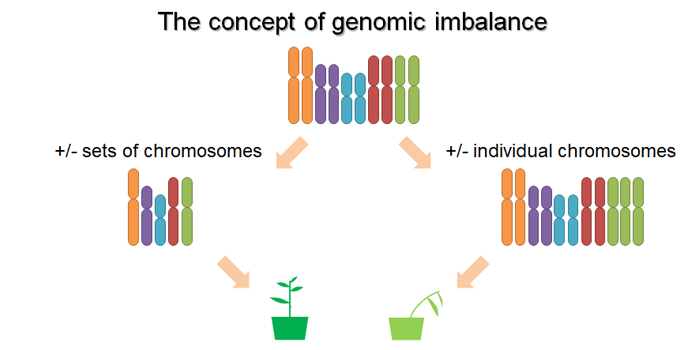

Gene Dosage Balance

Changes in gene dosage are a powerful and important driver of gene expression abundance, quantitative trait variation, and the evolution of genomes. It’s been widely observed that for certain classes of genes, especially those involved in highly connected regulatory networks and multimeric protein complexes, imbalanced propotions of gene products can have a large phenotypic impact and be highly deleterious. The need to maintain the stoichiometric balance of gene products in the face of changes in gene dosage influences genome evolution in important and predictable ways. In particular, duplicate copies from many transcription factor families, genes involved in signaling pathways and multimeric protein complexes, and others are retained more than expected after whole-genome duplication, and duplicates from tandem duplications are retained less than expected.

I investigated patterns of gene expression after whole-genome duplication and found immediate changes that reflect evolutionary constraint on dosage-sensitive genes. However, this constraint didn’t exist for gene pairs biased toward the non-dominant subgenome. I also demonstrated that when dosage-sensitive genes are affected homoeologous exchanges (physical replacement of orthologous regions from recombination among subgenomes) they too show signs of evolutionary constraint for balanced gene dosage.

I’m interested in extending this work to see how gene dosage relates to cases of epistasis in a network context and among gene duplicates, and the ways that constraint for gene dosage balance affects the evolution of diverse kinds of structural variants.

“Humane” Genomics

Genetics and evolutionary biology have a uniquely dark history due to their central role in justifying eugenics, colonialism, and racism. Moreover, misunderstandings about human genetics and evolution result in genetic essentialism, the belief that a “race” is a genetically homogenous grouping of people, and that races primarily differ physically, cognitively, and behaviorally because of genetic differences. In turn, genetic essentialism is associated with opposition to policies that promote racial equality.

Recent advances in genomics, like Genome-Wide Association Studies and polygenic scores, and the widespread availability of public databases have fueled a resurgence in scientific racism. Additionally, some mainstream research perpetuates overly simplistic and deterministic ideas about genetics that further facilitate racist misuse. As subject matter experts, there is an obligation for researchers trained in these fields to understand this history, how this history affects contemporary ideas and debates, and how to move the field and public understanding forward.

My work in this area has focused on three main aspects. First, I use methods from genetics and genomics to directly challenge racist hypotheses about genetics and racial differences, especially pertaining to the longstanding theories about IQ scores. Second, I focus on conceptual and methodological problems in mainstream research that contribute to biological determinism and reinforce genetic essentialism. Third, I work to create and implement biology curricula, rooted in pedagogical theory, that teach students the latest in genetics and evolution while explaining how cutting-edge science refutes genetic essentialism. Such curriculum has shown strong evidence of reducing racial prejudice in students and may also innoculate them from race science propaganda that is prevalent in some online communities.